Population Statistics for Zionist State, Haredim

Source: Ynet, BBC

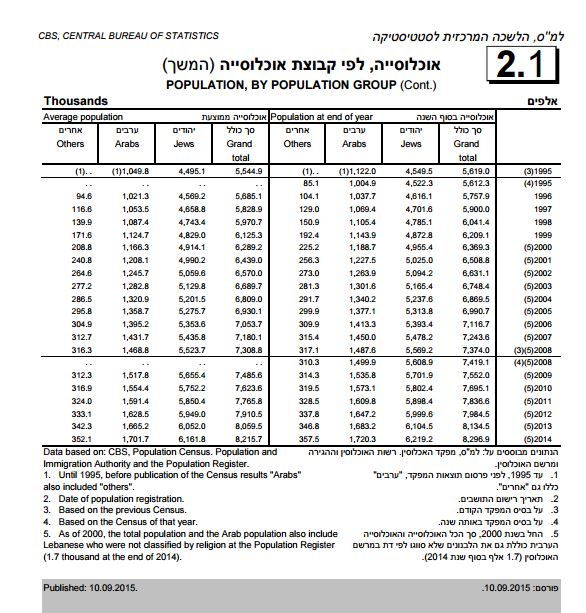

A special situation report presented by the Central Bureau of Statistics ahead of the Jewish New Year reveals that at the end of 2006, Israel had 7,116,700 million citizens living in its territory.

According to the report, released on Monday, the state's current population is divided among 5,393,400 Jews (75.8% of the population), 1,413,300 Arabs (19.9 % of the population), and about 309,900 citizens who are defined as "others" and are not classified according to religion.

The rate at which the population grew last year was 1.8%, similar to previous years. The Jewish population growth rate was 1.5% in 2006, compared to 2.6% among Arabs, with the Muslim population having the highest growth rate at 2.9%.

In a BBC article last week, Tim Franks wrote about the most religious segment of the Zionist state's Jewish population:

Jerusalem's central Haredi neighborhood, Mea Shearim, is witness to a looming demographic dilemma for Israel. The Haredim live in a world apart from modern, westernised West Jerusalem, devoting their lives to the study of Jewish law and thought.

It is widely accepted that Palestinian population growth in Israel and the occupied territories is a major strategic issue for Israel. But the proportion of ultra-orthodox Haredi Jews is also growing, approximately three times as fast as the rest of the population.

In a country where every 18-year-old Jew is supposed to join the army - and which has faced six major conflicts with its neighbours and battled two Palestinian uprisings - that Haredi population growth poses some urgent questions.

The ultra-orthodox do not face compulsory conscription; they are exempted from national service in order to continue their religious studies. Once it was a tiny minority which took that route; now they account for more than 10% of draft-age Israeli Jews. By 2019, the government forecasts they will constitute almost one in four.

Former Deputy Prime Minister Yosef (Tommy) Lapid represents a constituency in Israel that asks whether Haredi behaviour is not in fact undermining the Jewish state. "I have nothing against them because they are religious," says Mr Lapid. "I very much oppose the fact that they don't serve in the army. They represent G-d in G-d's country, but don't defend G-d's country".

From the yeshivas, or theological colleges, around Jerusalem, where the young men sway back and forth as they read and debate centuries of law and commentary, there is a different view. They believe that the country has spiritual as well as physical needs, and there is no greater service than that of religious study.

"If you look at the whole history of the Jewish people, it can't be explained in physical terms. What made us survive this long? We really believe G-d has a hand in history," says Haredi rabbi Moshe Zeldman.

Rabbi Zeldman says he is not living in a dreamland, where only G-d takes care of the Jews and Israel does not need an army. "You also need a balance. And the balance has to be that as much as you're worried about your physical survival, you're also focused on your spiritual survival," he says.

But there is a further source of tension - the economy. At a food distribution scheme in Mea Shearim, dozens of families come to collect cardboard boxes full of all types of kosher food. This is not an unusual sight, because most Haredim are poor and many rely heavily on welfare. Government figures suggest that two out of three Haredi men do not have a paid job. More and more, Israelis are asking if this too can carry on.

Demographer Menachem Friedman says that either the Haredim will have to change their ways or "the government will force them" to contribute more to the economy and defence. "To keep the status quo as it is now probably will not be possible," he says. "Everyone has to make a very crucial decision to change the situation. How they will make it, I don't know." It is one of the most difficult questions of all for Israel - what a Jewish state should demand of its own Jewish citizens.

Here is yet another case of a report in the mainstream media that misses the point of religious opposition to the Zionist state. Most Haredim are opposed to army service because they are opposed to the existence and continuation of the state defended by that army. They follow Jewish law as expounded in the Talmud, which states that Jews are currently in exile and are forbidden from fighting wars against non-Jewish nations. In order to avoid the draft, the young men in the Haredi community must remain involved in full-time religious studies, which means being unemployed.

The hardship of having two thirds of men unemployed is becoming increasing unbearable, as the article correctly points out. However, the article suggests that this unemployment is the ideology of the Haredim, when in truth it is a hardship forced on them by the Zionist government's conscription laws. If the Zionists want this community to become more productive and less dependent, they should recognize their identity as a separatist community wanting no part in the state and its military exploits, and release their young men completely from the draft regardless of whether they are studying or working.

It is true that the term "Haredi" simply means "religious Jews" and is not synonymous with anti-Zionists. Indeed there are some today who call themselves "Haredi Zionists". Other Haredi groups will not openly call themselves Zionists but adopt an essentially apologetic style when dealing with Zionism, saying in effect, "We also agree that you need a state and an army, but you need spirituality too." However, these Haredi Zionists do not represent the majority of Haredim, and we are disappointed to see that BBC is giving their view exclusive coverage.